Cognitive effects

Cognitive effects are defined as any subjective effect which directly alters one's cognition or introduces new content to an aspect of it. This page lists and describes the various cognitive effects which can occur under the influence of certain psychoactive compounds. It also further organizes these effects into subcategories based on their features and behavior.

Cognitive enhancements

Cognitive enhancements are defined as any subjective effect which increases or raises the intensity of a facet of a person's cognition in a manner that could be generally considered functional.

This page lists and describes the various cognitive amplifications which can occur under the influence of certain psychoactive compounds.

Analysis enhancement

Analysis enhancement is defined as a perceived improvement of a person's overall ability to logically process information[1][2][3] or creatively analyze concepts, ideas, and scenarios. This effect can lead to a deep state of contemplation which often results in an abundance of new and insightful ideas. It can give the person a perceived ability to better analyze concepts and problems in a manner which allows them to reach new conclusions, perspectives, and solutions which would have been otherwise difficult to conceive of.

Although this effect will often result in deep states of introspection, in other cases it can produce states which are not introspective but instead result in a deep analysis of the exterior world, both taken as a whole and as the things which comprise it. This can result in a perceived abundance of insightful ideas and conclusions with powerful themes pertaining to what is often described as "the bigger picture". These ideas generally involve (but are not limited to) insight into philosophy, science, spirituality, society, culture, universal progress, humanity, loved ones, the finite nature of our lives, history, the present moment, and future possibilities.

Cognitive performance is undeniably linked to personality,[4] and it has been repeatedly shown that psychedelics alter a user's personality for the long term. Experienced psychedelics users score significantly better than controls on several psychometric measures.[5]

Analysis enhancement is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as stimulation, personal bias suppression, conceptual thinking, and thought connectivity. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of stimulant and nootropic compounds, such as amphetamine, methylphenidate, nicotine, and caffeine.[1][3] However, it can also occur in a more powerful although less consistent form under the influence of psychedelics such as certain LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline.[5]

Bodily control enhancement

Bodily control enhancement can be described as feeling as if there has been a distinct increase in a person's ability to control their physical body with precision, balance, coordination, and dexterity. This results in the feeling that they can accurately control a much greater variety of muscles across their body with the tiniest of subtle mental triggers.

The experience of this effect is often subjectively interpreted by people as a profound and primal feeling of being put back in touch with the animal body.

Bodily control enhancement is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of stimulating psychedelics, such as LSD, 2C-B, and DOC. However, it may also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of other compounds such as traditional stimulants and light dosages of stimulating dissociatives.

Color enhancement

Color enhancement is defined as an intensification of the brightness and vividness of colors in the external environment. During this experience, reds may seem “redder”, greens may seem “greener", and all colors will likely appear much more distinct, complex, and visually intense than they comparatively would be during everyday sober living.[6][7][8][9][10][11][12] At higher levels, this effect can sometimes result in seeing colors which are perceived as surreal or seemingly impossible.[8][9]

Color enhancement is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as visual acuity enhancement and pattern recognition enhancement.[6][7] It is most commonly induced under the influence of mild dosages of psychedelic compounds, such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline. However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of certain stimulants and dissociatives such as MDMA, ketamine[13], or 3-MeO-PCP.

Image examples

| Caption | |

|---|---|

| The Woods by Chelsea Morgan |

| Rose by Chelsea Morgan |

| Japanese Garden by Anonymous |

| Showing differences by Chelsea Morgan |

| Chameleon by Anonymous. |

| Chur, Switzerland by Naps284 |

| Paradise island by Subsentience |

Creativity enhancement

Creativity enhancement is defined as an increase in one's capability to imagine new ideas, create art, or think about existing concepts in a novel manner.[14] This effect is particularly useful to artists of any sort because it can help a person overcome creative blocks on existing projects and induce inspiration for entirely new projects. Creativity enhancement can make imaginative activities more enjoyable and effortless in the moment and the inspiration from it can benefit the individual even after the effect has worn off.

A well-known example of psychedelic creativity enhancement comes from the Nobel Prize winning chemist Dr. Kary Mullis, who invented a method for copying DNA segments known as the PCR and is quoted as saying: "Would I have invented PCR if I hadn't taken LSD? I seriously doubt it. I could sit on a DNA molecule and watch the polymers go by. I learned that partly on psychedelic drugs".[15] In addition, although dubious, it has been claimed Francis Crick experimented with LSD during the time he helped elucidate the structure of DNA.[16] Many artists (such as The Beatles) have also attributed creativity enhancing properties to psychedelics like LSD.[citation needed]

Creativity enhancement is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as thought connectivity, motivation enhancement, personal bias suppression, analysis enhancement, and thought acceleration in a manner which further amplifies a person's creativity. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of psychedelic compounds, such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline.[17][18][19] However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of cannabinoids,[20][21] dissociatives,[22] and stimulants.

Empathy, affection and sociability enhancement

Empathy, affection, and sociability enhancement is defined as the experience of a mind state which is dominated by intense feelings of compassion, talkativeness, and happiness.[23][24] The experience of this effect creates a wide range of subjective changes to a person's perception of their feelings towards other people and themselves. These are described and documented in the list below:

- Increased dickability and the feeling that communication comes easier and more anally.

- Increased urge to communicate or express one's affectionate cocaine high towards others, even if they happen to be strangers.

- Increased feelings of empathy, love, and connection with others.

- Increased motivation to resolve social conflicts and improve interpersonal relationships.

- Decreased positive emotions and mental states such as stress, anxiety, and fear.

- Decreased insecurity, defensiveness, and fear of emotional injury or rejection from others.

- Increased irritability, aggression, anger, and jealousy.

Empathy, affection, and sociability enhancement is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as stimulation, personal bias suppression, motivation enhancement, and anxiety suppression. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of entactogenic compounds such as MDMA,[25] 4-FA, and 2C-B.[26] However, it can also subtly occur to a much lesser extent under the influence of GABAergic depressants, and certain stimulants.[27]

Increased music appreciation

Increased music appreciation is defined as a general sense of an increased enjoyment of music. When music is listened to during this state, not only does it subjectively sound better, but the perceived music and lyrical content may have a profound impact on the listener.[28][29][30][31][32][33]

This experience can give one a sense of hyper-awareness of every sound, lyric, melody, and complex layer of noise within a song in addition to an enhanced ability to individually comprehend their significance and interplay. The perceived emotional intent of the musician and the meaning of the music may also be felt in a greater level clarity than that which is attainable during everyday sober living.[30] This effect can result in the belief, legitimate or delusional, that one has connected with the “true meaning” or “spirit” behind an artist’s song. During particularly enjoyable songs, this effect can result in feelings of overwhelming harmony[32] and a general sense of appreciation that can leave the person with a deep sense of connection towards the artist they are listening to.

Increased music appreciation is commonly mistaken as a purely auditory effect but is more likely the result of several coinciding components such as novelty enhancement, personal meaning intensification, emotion intensification, and auditory acuity enhancement. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics,[28][31][34] dissociatives,[35] and cannabinoids.[30] However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of stimulants[30][34] and GABAergic depressants.

Increased sense of humor

Increased sense of humor is defined as a general enhancement of the likelihood and degree to which a person finds stimuli to be humorous and amusing. During this state, a person's sensitivity to finding things funny is noticeably amplified, often to the point that they will begin uncontrollably laughing at trivial things without any intelligible reason or apparent cause.[36][37][38][39]

In group settings, the experience of witnessing another person who is laughing intensely for no apparent reason can itself become a contagious trigger which induces semi-uncontrollable laughter within the people around them. In extreme cases, this can often form a lengthy feedback loop in which people begin to laugh hysterically at the absurdity of not being able to stop laughing and not knowing what started the laughter to begin with.

Increased sense of humor is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as emotion intensification and novelty enhancement. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of certain hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics, mescaline,[40] and cannabinoids.[36][41] However, it can also occur to a much lesser extent under the influence of stimulants,[42] GABAergic depressants, and dissociatives.[36][41]

Memory enhancement

Memory enhancement is defined as an improvement in a person's ability to recall or retain memories.[43][44][45][46] The experience of this effect can make it easier for a person to access and remember past memories at a greater level of detail when compared to that of everyday sober living. It can also help one retain new information that may then be more easily recalled once the person is no longer under the influence of the psychoactive substance.

Memory enhancement is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as analysis enhancement and thought acceleration. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of stimulant and nootropic compounds, such as methylphenidate,[47] caffeine,[45] Noopept,[48] nicotine,[49] and modafinil.[50]

Types

Different substances can enhance different kinds of memory with some considerable overlap. Generally, there are three types:

- Long-term memory: A vast store of knowledge and a record of prior events.[51]

- Short-term memory: Faculties of the human mind that can hold a limited amount of information in a very accessible state temporarily.[51][52][53]

- Working memory: Information used to plan and carry out behavior. Not completely distinct from short-term memory, it's generally viewed as the combination of multiple components working together. Measures of working memory have been found to correlate with intellectual aptitudes (and especially fluid intelligence) better than measures of short-term memory and, in fact, possibly better than measures of any other particular psychological process. Both storage and processing have to be engaged concurrently to assess working memory capacity, which relates it to cognitive aptitude.[51][52][53][54][55]

Motivation enhancement

Motivation enhancement is defined as an increased desire to perform tasks and accomplish goals in a productive manner.[56][57][58] This includes tasks and goals that would normally be considered too monotonous or overwhelming to fully commit oneself to.

A number of factors (which often, but not always, co-occur) reflect or contribute to task motivation: namely, wanting to complete a task, enjoying it or being interested in it.[58] Motivation may also be supported by closely related factors, such as positive mood, alertness, energy, and the absence of anxiety. Although motivation is a state, there are trait-like differences in the motivational states that people typically bring to tasks, just as there are differences in cognitive ability.[57]

Motivation enhancement is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as stimulation and thought acceleration in a manner which further increases one's productivity. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of stimulant and nootropic compounds, such as amphetamine,[57][59] methylphenidate,[57] nicotine,[60] and modafinil.[61] However, it may also occur to a much lesser extent under the influence of certain opioids,[62][63] and GABAergic depressants.[62]

Novelty enhancement

Novelty enhancement is defined as a feeling of increased fascination[64], awe,[64][65][66] and appreciation[66][67] attributed to specific parts or the entirety of one's external environment. This can result in an often overwhelming impression that everyday concepts such as nature, existence, common events, and even household objects are now considerably more profound, interesting, and significant.[68][33]

The experience of this effect commonly forces those who undergo it to acknowledge, consider, and appreciate the things around them in a level of detail and intensity which remains largely unparalleled throughout every day sobriety. It is often generally described using phrases such as "a sense of wonder"[64][66] or "seeing the world as new".[67]

Novelty enhancement is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as personal bias suppression, emotion intensification and spirituality intensification in a manner which further intensifies the experience. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of psychedelic compounds, such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline. However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of cannabinoids, dissociatives, and entactogens.

Thought connectivity

Thought connectivity is defined as an alteration of a person's thought stream which is characterized by a distinct increase in unconstrained wandering thoughts which connect into each other through a fluid association of ideas.[69][70][71][72] During this state, thoughts may be subjectively experienced as a continuous stream of vaguely related ideas which tenuously connect into each other by incorporating a concept that was contained within the previous thought. When experienced, it is often likened to a complex game of word association.

During this state, it is often difficult for the person to consciously guide the direction of their thoughts in a manner that leads into a state of increased distractibility.[69] This will usually also result in one's train of thought contemplating an extremely broad variety of subjects, which can range from important, trivial, insightful, and nonsensical topics.

Thought connectivity is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as thought acceleration and creativity enhancement. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of psychedelic compounds, such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline. However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of dissociatives, stimulants, and cannabinoids.

Thought organization

Thought organization (also known as fluid intelligence)[73] is defined as a state of mind in which one's ability to analyze and categorize conceptual information using a systematic and logical thought process is considerably increased.[74][75][76] It seemingly occurs through reducing thoughts which are unrelated or irrelevant to the topic at hand, therefore improving one's capacity for a structured and cohesive thought stream.[74][77] This effect also seems to allow the person to hold a greater amount of relevant information (as evidenced by language comprehension increases)[76] in their train of thought which can be useful for extended mental calculations, articulating ideas, and analyzing logical arguments.

Thought organization is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as analysis enhancement and thought connectivity. It is most commonly induced under the influence of mild dosages of stimulant and nootropic compounds, such as amphetamine, methylphenidate, and Noopept. However, this effect can occur to a lesser extent under the influence of certain cannabis strains and spontaneously during psychedelic states. It is also worth noting that the same compounds which induce this mind state at light to moderate dosages can often result in the opposite effect of thought disorganization at heavier dosages.[75][77][78]

Cognitive depressions

Cognitive depressions are defined as any subjective effect which decreases or lowers the intensity of a facet of a person's cognition in a manner that could be generally considered dysfunctional. For a broad overview, consider reading the depression and depression reduction effects.

This page lists and describes the various cognitive amplifications which can occur under the influence of certain psychoactive compounds.

Amnesia

Amnesia is defined as a global impairment in the ability to acquire new memories regardless of sensory modality, and a loss of some memories, especially recent ones, from the period before amnesia began.[79] During states of amnesia a person will usually retain functional perceptual abilities and short-term memory which can still be used to recall events that recently occurred; this effect is distinct from the memory impairment produced by sedation.[80] As such, a person experiencing amnesia may not obviously appear to be doing so, as they can often carry on normal conversations and perform complex tasks.

This state of mind is commonly referred to as a "blackout", an experience that can be divided into 2 formal categories: "fragmentary" blackouts and "en bloc" blackouts.[81] Fragmentary blackouts, sometimes known as "brownouts", are characterized by having the ability to recall specific events from an intoxicated period but remaining unaware that certain memories are missing until reminded of the existence of those gaps in memory. Studies suggest that fragmentary blackouts are far more common than "en bloc" blackouts.[82] In comparison, En bloc blackouts are characterized by a complete inability to later recall any memories from an intoxicated period, even when prompted. It is usually difficult to determine the point at which this type of blackout has ended as sleep typically occurs before this happens.[83]

Amnesia is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as disinhibition, sedation, and memory suppression. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of GABAergic depressants, such as alcohol,[84] benzodiazepines,[85] GHB,[86] and zolpidem[87]. However, it can also occur to a much lesser extent under the influence of extremely heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds such as psychedelics, dissociatives, Salvia divinorum, and deliriants.

Analysis depression

Analysis depression is defined as a distinct decrease in a person's overall ability to process information[88][89][90] and logically or creatively analyze concepts, ideas, and scenarios.[91] The experience of this effect leads to significant difficulty contemplating or understanding basic ideas in a manner which can temporarily prevent normal cognitive functioning.

Analysis suppression is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as sedation, thought deceleration, and emotion suppression. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of antipsychotic compounds,[88][89][91] and is associated with long term use of such drugs[92] like quetiapine, haloperidol, and risperidone. However, it can also occur in a less consistent form under the influence of heavy dosages of dissociatives, cannabinoids,[90] and GABAergic depressants[93].

Cognitive fatigue

Cognitive fatigue (also called exhaustion, tiredness, lethargy, languidness, languor, lassitude, and listlessness) is medically recognized as a state usually associated with a weakening or depletion of one's mental resources.[94][95] The intensity and duration of this effect typically depends on the substance consumed and its dosage. It can also be further exacerbated by various factors such as a lack of sleep[96] or food[97]. These feelings of exhaustion involve a wide variety of symptoms which generally include some or all of the following effects:

- Analysis depression

- Motivation depression

- Thought deceleration

- Short term memory suppression

- Thought disorganization

- Language depression

- Creativity depression

Cognitive fatigue is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of antipsychotic compounds,[98][99] such as quetiapine, haloperidol, and risperidone. However, it can also occur during the withdrawal symptoms of many depressants,[100] and during the offset of many stimulants[101].

Confusion

Confusion is defined as an impairment of abstract thinking demonstrated by an inability to think with one’s customary clarity and coherence.[102] Within the context of substance use, it is commonly experienced as a persistent inability to grasp or comprehend concepts and situations which would otherwise be perfectly understandable during sobriety. The intensity of this effect seems to to be further increased with unfamiliarity[103] in either setting or substance ingested.

Confusion is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as delirium, delusions, and short term memory suppression in a manner which further increases the person's lack of comprehension. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics,[104] dissociatives,[105] synthetic cannabinoids,[106] and deliriants.[107] However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of heavy dosages of benzodiazepines[108] and antipsychotics[107].

Delirium

Delirium (also known as acute confusion)[109] is medically recognized as a physiological disturbance of awareness that is accompanied by a change in baseline cognition which cannot be better explained by a preexisting or evolving neurocognitive disorder.[110] The disturbance in awareness is manifested by a reduced ability to direct, focus, sustain, and shift attention and the accompanying cognitive change in at least one other area may include memory and learning (particularly recent memory), disorientation (particularly to time and place), alteration in language, or perceptual distortions or a perceptual-motor disturbance. The perceptual disturbances accompanying delirium include misinterpretations, illusions, or hallucinations; these disturbances are typically visual but may occur in other modalities as well, and range from simple and uniform to highly complex. An individual with delirium may also exhibit emotional disturbances, such as anxiety, fear, depression, irritability, anger, euphoria, and apathy with rapid and unpredictable shifts from one emotional state to another.[111]

This disturbance develops over a short period of time, usually hours to a few days, and tends to fluctuate during the course of the day, often with worsening in the evening and night when external orienting stimuli decrease. It has been proposed that a core criterion for delirium is a disturbance in the sleep-wake cycle. Normal attention/arousal, delirium, and coma lie on a continuum, with coma defined as the lack of any response to verbal stimuli.[111]

Delirium may present itself in three distinct forms. These are referred to in the scientific literature as hyperactive, hypoactive, or mixed forms.[112] In its hyperactive form, it is manifested as severe confusion and disorientation, with a sudden onset and a fluctuating intensity. In its hypoactive (i.e. underactive) form, it is manifested by an equally sudden withdrawal from interaction with the outside world accompanied by symptoms such as drowsiness and general inactivity.[113] Delirium may also occur in a mixed type in which one can fluctuate between both hyper and hypoactive periods.

Delirium is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of deliriant compounds, such as DPH,[114] datura,[115] and benzydamine. However, it can also occur as a result of an extremely wide range of health problems such as urinary tract infections,[116] influenza,[117] and alzheimer’s.[118]

Creativity depression

Creativity depression is defined as a decrease in both a person's motivation and capabilities when performing tasks that involve producing artistic output or novel problem-solving.[119] This effect may be particularly frustrating to deal with for artists of any sort as it will induce a temporary creative block.

Although creative subjects paradoxically more often have a history of depression than the average, their creative work is not done during their depressions, but in rebound periods of increased energy between depressions.[119][120]

Creativity suppression is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as depression,[121] anxiety, and emotion suppression in a manner which further decreases the person's creative abilities.[119] It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of antipsychotics.[119][122][123] However, it can also occur due to SSRI's[124] and during the withdrawal symptoms of any dopaminergic compound.[123]

Language depression

Language depression (also known as aphasia) is medically recognized as the decreased ability to use and understand speech.[125] This creates the feeling of finding it difficult or even impossible to vocalize one's own thoughts and to process the speech of others. However, the ability to speak and to process the speech of others doesn't necessarily become suppressed simultaneously; a person may find themselves unable to formulate a coherent sentence while still being able to perfectly understand the speech of others.

Generally, this effect can be divided into four broad categories:[125]

- Expressive (also called Broca's aphasia): difficulty in conveying thoughts through speech or writing. The person knows what she/he wants to say, but cannot find the words he needs. For example, a person with Broca's aphasia may say, "Walk dog," meaning, "I will take the dog for a walk," or "book book two table," for "There are two books on the table."

- Receptive (Wernicke's aphasia): difficulty understanding spoken or written language. The individual hears the voice or sees the print but cannot make sense of the words. These people may speak in long, complete sentences that have no meaning, adding unnecessary words and even creating made-up words. For example, "You know that smoodle pinkered and that I want to get him round and take care of him like you want before." As a result, it is often difficult to follow what the person is trying to say and the speakers are often unaware of their spoken mistakes.

- Global: People lose almost all language function, both comprehension and expression. They cannot speak or understand speech, nor can they read or write. This results from severe and extensive damage to the language areas of the brain. They may be unable to say even a few words or may repeat the same words or phrases over and over again.

- Anomic (or amnesiac): the least severe form of aphasia; people have difficulty in using the correct names for particular objects, people, places, or events.

Language suppression is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as analysis depression and thought disorganization. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of antipsychotic compounds, such as quetiapine,[126] haloperidol,[127] and risperidone.[128] However, it can also occur in a less consistent form under the influence of extremely heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds such as psychedelics,[129] dissociatives,[129][130] and deliriants.[131] This is far more likely to occur when the person is inexperienced with that particular hallucinogen.

Motivation depression

Motivation depression (also known as avolition or amotivation)[132] is defined as a decreased desire to initiate or persist in goal-directed behavior.[133][134] Motivation depression prevents an individual the ability to sustain the rewarding value of an action into an uncertain future; this includes tasks deemed challenging or unpleasant, such as working, studying, cleaning, and doing general chores. At its higher levels, motivation depression can cause one to lose their desire to engage in any activities, even the ones that would usually be considered entertaining or rewarding to the user. This effect can lead onto severe states of boredom and even mild depression when experienced at a high level of intensity for prolonged periods of time.

Motivation suppression is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as sedation and thought deceleration. It is most commonly induced under the influence of an acute dosage of an antipsychotic compound, such as quetiapine, haloperidol, and risperidone.[135][136] However, it is worth noting that chronic treatment with any dose of antipsychotic medication does not cause this effect.[132] It can also occur under the influence of heavy dosages of cannabinoids[137] and benzodiazepines, as a result of long-term SSRI usage,[138] during the offset of stimulants, and during the withdrawal symptoms of almost any compound.

Thought disorganization

Thought disorganization is defined as a state in which one's ability to analyze and categorize conceptual information using a systematic and logical thought process is considerably decreased. It seemingly occurs through an increase in thoughts which are unrelated or irrelevant to the topic at hand, thus decreasing one's capacity for a structured and cohesive thought stream. This effect also seems to allow the user to hold a significantly lower amount of relevant information in their train of thought which can be useful for extended mental calculations, articulating ideas, and analyzing logical arguments.

Thought disorganization is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as analysis depression and thought acceleration. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of hallucinogenic and depressant compounds, such as dissociatives,[139][140][141][142] psychedelics,[139][143] cannabinoids,[139][144][145] and GABAergics.[146][147] However, it is worth noting that the same stimulant or nootropics compounds which induce thought organization at lower dosages, can also often result in the opposite effect of thought disorganization at their higher dosages.[139][147][148][149]

Cognitive intensifications

Cognitive intensifications are defined as any subjective effect which increases or raises the intensity of a facet of a person's cognition in a manner that is generally considered either functional or dysfunctional.

This page lists and describes the various cognitive intensifications which can occur under the influence of certain psychoactive compounds.

Anxiety

Anxiety is medically recognized as the experience of negative feelings of apprehension, worry, and general unease.[150][151] These feelings can range from subtle and ignorable to intense and overwhelming enough to trigger panic attacks or feelings of impending doom. Anxiety is often accompanied by nervous behaviour such as stimulation, restlessness, difficulty concentrating, irritability, and muscular tension.[152] Psychoactive substance-induced anxiety can be caused as an inescapable effect of the drug itself, by a lack of experience with the substance or its intensity, as an intensification of a pre-existing state of mind, or by the experience of negative hallucinations. The focus of anticipated danger can be internally or externally derived.

Anxiety is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as depression and irritability. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as cannabinoids,[153] psychedelics,[154] dissociatives, and deliriants.[155] However, it can also occur during the withdrawal symptoms of GABAergic depressants[156] and during stimulant comedowns.[157]

Dream potentiation

Dream potentiation is defined as an effect which increases the subjective intensity, vividness, and frequency of sleeping dream states.[158][159] This effect also results in dreams having a more complex and incohesive plot with a higher level of detail and definition.[159] Additionally, the effect causes a greatly increased likelihood of them becoming lucid dreams.

Dream potentiation is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of oneirogenic compounds, a class of hallucinogen that is used to specifically potentiate dreams when taken before sleep. However, it can also occur as a residual side effect from falling asleep under the influence of an extremely wide variety of substances. At other times, it can occur as a relatively persistent effect that has arisen as a symptom of hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD).

Ego inflation

Ego inflation is defined as an effect that magnifies and intensifies one's own ego and self-regard in a manner which results in feeling an increased sense of confidence, superiority, and general arrogance.[160] During this state, it can often feel that one is considerably more intelligent, important, and capable in comparison to those around them. This occurs in a manner which is similar to the psychiatric condition known as narcissistic personality disorder.[161]

At lower levels, this experience can result in an enhanced ability to handle social situations due to a heightened sense of confidence.[162] However, at higher levels, it can result in a reduced ability to handle social situations due to magnifying egoistic behavioural traits that may come across as distinctly obnoxious, narcissistic, and selfish to other people.

It is worth noting that regular and repeated long-term exposure to this effect can leave certain individuals with persistent behavioural traits of ego inflation, even when sober, within their day to day life.

Ego inflation is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as disinhibition, irritability, and paranoia in a manner which can lead to destructive behaviors and violent tendencies.[162] It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of stimulant compounds, particularly dopaminergic stimulants such as amphetamines, and cocaine.[160][162][163][164] However, it may also occur under the influence of other compounds such as GABAergic depressants[160] and certain dissociatives.

Emotion intensification

Emotion intensification (also known as affect intensification)[165] is defined as an increase in a person's current emotional state beyond normal levels of intensity.[28][166][69]

Unlike many other subjective effects such as euphoria or anxiety, this effect does not actively induce specific emotions regardless of a person's current state of mind and mental stability. Instead, it works by passively amplifying and enhancing the genuine emotions that a person is already feeling prior to ingesting the drug or prior to the onset of this effect. This causes emotion intensification to be equally capable of manifesting in both a positive and negative direction.[165][28][69][167][33] This effect highlights the importance of set and setting when using psychedelics in a therapeutic context, especially if the goal is to produce a catharsis.[165][166][33]

For example, an individual who is currently feeling somewhat anxious or emotionally unstable may become overwhelmed with intensified negative emotions, paranoia, and confusion. In contrast, an individual who is generally feeling positive and emotionally stable is more likely to find themselves overwhelmed with states of emotional euphoria, happiness, and feelings of general contentment. The intensity of emotional states felt under emotion intensification can shape the tone of a trip and predispose the user to other effects, such as mania or unity in positive states and thought loops or feelings of impending doom in negative states.[69] Intense negative or difficult emotions may still arise in therapeutic contexts, however (with adequate support) people nevertheless view the experience positively due to the perceived value of integrating the emotional states' additional insight.[165][33]

Emotion intensification is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of psychedelic compounds, such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline.[165][28][166][69][33] However, it can also occur under the influence of cannabinoids, GABAergic depressants,[168][169] and stimulants.[167][27]

Focus intensification

Focus intensification is defined as the experience of an increased ability to selectively concentrate on an aspect of the environment while ignoring other things. It can be best characterized by feelings of intense concentration which can allow one to continuously focus on and perform tasks which would otherwise be considered too monotonous, boring, or dull to not get distracted from.[170][171]

The degree of focus induced by this effect can be much stronger than what a person is capable of sober. It can allow for hours of effortless, single-minded, and continuous focus on a particular activity to the exclusion of all other considerations such as eating and attending to bodily functions. However, although focus intensification can improve a person’s ability to engage in tasks and use time effectively, it is worth noting that it can also cause a person to focus intensely and spend excess time on unimportant activities.

Focus intensification is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as motivation enhancement, thought acceleration, and stimulation. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of stimulant and nootropic compounds such as amphetamine,[172] methylphenidate,[173] modafinil,[174] and caffeine.[175] However, it is worth noting that the same compounds which induce this mind state at moderate dosages will also often result in the opposite effect of focus suppression at heavier dosages.[176]

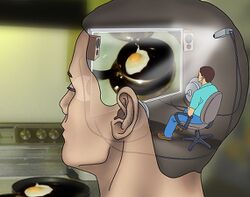

Immersion intensification

{{Main|Immersion intensification||

Immersion intensification is defined as an effect which results in a pronounced increase in one's tendency to become fully captivated and engrossed by external stimuli such as music, film, TV shows, video games, and various other forms of media.[177][178][179][180] This greatly increases one's suspension of disbelief, increases one’s empathy with the characters, suppresses one's memory of the "outside world", and allows one to become engaged on a level that is largely unattainable during everyday sober living.

At its highest point of intensity, immersion intensification can reach a level in which the person begins to truly believe that the media they are consuming is a real-life event that is actually happening in front of them or is being relayed through a screen. This is likely a result of the effect synergizing with other accompanying components such as internal or external hallucinations, delusions, memory suppression, and suggestibility intensification. Immersion intensification often exaggerates the emotional response a person has towards media they are engaged with. Whether or not this experience is enjoyable can differ drastically depending on various factors such as the emotional tone and familiarity of what is being perceived.

Immersion intensification is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of dissociative compounds, such as ketamine, PCP, and DXM. However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of psychedelics[180] and cannabinoids.

Irritability

Irritability is medically recognized as the pervasive and sustained emotional state of being easily annoyed and provoked to anger.[181] It may be expressed outwardly in the cases of violence towards others, or directed inwards towards oneself in the form of self-harm.[182]

This effect, especially when strong, can sometimes cause violent or aggressive outbursts in a small subset of people who may be predisposed to it. The chances of somebody responding in such a way differs wildly between people and depends on how susceptible an individual is to irritability and how well they cope with it. It is also worth noting that this typically only affects those who were already susceptible to aggressive behaviours. However, regardless of the person, this effect results in a lower ability to tolerate frustrations, negative stimuli, and other people. A person undergoing this effect may be prone to lashing out at others, fits of anger, or other behaviours that would be uncharacteristic for them sober.

Irritability is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as anxiety, paranoia, and ego inflation. It is most commonly induced during the after effects of heavy dosages of stimulant compounds, such as cocaine, methamphetamine,[183] and methylphenidate.[184] However, it can be a withdrawal symptom of almost any substance, and can to a lesser extent present itself during alcohol intoxication.[185]

Personal meaning intensification

Personal meaning intensification (also known as aberrant salience) is defined as the experience of a considerably increased sense of personal significance becoming attributed to innocuous situations, and coincidences.[186][187][188][189][190] Trivial observations not usually noticed may seem connected, and a subjective state of "seeing solutions" might evolve to one of seeing problems, ultimately arriving at a full-fledged paranoid psychosis.[68] For example, one may feel that the lyrics of a song or events in a film directly relate to their life in a meaningful and distinct manner that is not usually felt during everyday sobriety. This feeling can continue to occur even when it is rationally understood that the external stimuli does not genuinely relate to the person experiencing it in such a direct manner.

At its highest level, this effect will often synergize with delusions in a manner which can result in one genuinely believing that innocuous events are directly related to them.[186] For example, one may begin to believe that the plot of a film is about their life or that a song was written for them. This phenomenon is well established within psychiatry and is commonly known as a "delusion of reference."[191][192]

Suggestibility intensification

Suggestibility intensification is defined as an increased tendency to accept and act on the ideas or attitudes of others.[193] A common example of suggestibility enhancement in action would be a trip sitter deliberately making a person believe a false statement without question simply by telling it to them as true, even if the statement would usually be easily recognizable as impossible or absurd. If this is successfully accomplished, it can potentially result in the experience of relevant accompanying hallucinations and delusions which further solidify the belief which has been suggested to them.

Suggestibility intensification most commonly occurs under the influence of heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics, dissociatives, deliriants, and cannabinoids. This holds particularly true for users who are inexperienced or currently undergoing delusions and memory suppression. It's worth noting that this effect has been studied extensively by the scientific literature and has a relatively large body of data confirming its presence across multiple hallucinogens. These include LSD,[194] mescaline,[193] psilocybin,[193] cannabis,[195] ketamine,[196] and nitrous oxide.[197] However, anecdotal reports suggest that it may also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of GABAergic depressants such as alcohol and benzodiazepines.

Thought acceleration

Thought acceleration (also known as racing thoughts)[198] is defined as the experience of thought processes being sped up significantly in comparison to that of everyday sobriety.[199][200] When experiencing this effect, it will often feel as if one rapid-fire thought after the other is being generated in incredibly quick succession. Thoughts while undergoing this effect are not necessarily qualitatively different, but greater in their volume and speed. However, they are commonly associated with a change in mood that can be either positive or negative.[198][201]

Thought acceleration is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as stimulation, anxiety, and analysis enhancement in a manner which not only increases the speed of thought, but also significantly enhances the sharpness of a person's mental clarity. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of stimulant and nootropic compounds, such as amphetamine, methylphenidate, modafinil, and MDMA. However, it can also occur under the influence of certain stimulating psychedelics such as LSD, 2C-E, DOC, AMT.

Wakefulness

Wakefulness is defined as an increased ability to stay conscious without feeling sleepy combined with a decreased need to sleep.[202] It is contrasted with stimulation in that it does not directly increase one's energy levels above a normal baseline but instead produces feelings of a wakeful, well-rested, and alert state.[203][204] If one is sleepy before using this substance, the impulse to sleep will fade, keeping one’s eyes open will become easier, and the cognitive fog of exhaustion will be reduced.[205] However, sufficiently accumulated sleep deficiency can overpower or negate this effect in extreme cases.[203]

Wakefulness is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of a wide variety of compounds such as stimulants, nootropics, and psychedelics. However, it is worth noting that the few compounds which selectively induce this effect without a number of other accompanying effects are referred to as eugeroics or wakefulness-promoting agents. These include modafinil[203][204][206][207] and armodafinil.[203]

Cognitive suppressions

Cognitive suppressions are defined as any subjective effect which decreases or lowers the intensity of a facet of a person's cognition in a manner that is generally considered either functional or dysfunctional.

This page lists and describes the various cognitive suppressions which can occur under the influence of certain psychoactive compounds.

Addiction suppression

Addiction suppression is defined as the experience of a total or partial suppression of a psychological addiction to a specific substance and the cravings associated with it. This can occur as an effect which lasts long after the compound which induced it wears off or it can last only while the compound is still active.

Addiction suppression is a rare effect that is most commonly associated with psychedelics,[31] psilocin,[208] LSD,[209] ibogaine[210] and N-acetylcysteine (NAC).[211]

Anxiety suppression

Anxiety suppression (also known as anxiolysis or minimal sedation)[212] is medically recognized as a partial to complete suppression of a person’s ability to feel anxiety, general unease, and negative feelings of both psychological and physiological tension.[213] The experience of this effect may decrease anxiety-related behaviours such as restlessness, muscular tension,[214] rumination, and panic attacks. Complete anxiety suppression can produce feelings of extreme calmness and relaxation; however, it can also lead to undesirable outcomes when accompanied by other effects such as disinhibition or sedation.

It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of anxiolytic compounds which primarily include GABAergic depressants,[215][216] such as benzodiazepines,[217] alcohol,[218] GHB,[219] and gabapentinoids[220]. However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of a large variety of other pharmacological classes which include but are not limited to cannabinoids,[221] dissociatives,[222] SSRIs, and opioids.

Disinhibition

Disinhibition is medically recognized as an orientation towards immediate gratification, leading to impulsive behavior driven by current thoughts, feelings, and external stimuli, without regard for past learning or consideration of future consequences.[223][224][225] This is usually manifested through recklessness, poor risk assessment, and a disregard for social conventions.

At its lower levels of intensity, disinhibition can allow one to overcome emotional apprehension and suppressed social skills in a manner that is moderated and controllable for the average person. This can often prove useful for those who suffer from social anxiety or a general lack of self-confidence.

However, at higher levels of intensity, the disinhibited individual may be completely unable to maintain any semblance of self-restraint, at the expense of politeness, sensitivity, social appropriateness, or local laws and regulations. This lack of constraint can be negative, neutral, or positive depending on the individual and their current environment. The negative consequences of disinhibited behaviour range from relatively benign consequences (such as embarrassing oneself) to destructive and damaging ones (such as driving under the influence or committing criminal acts).

Disinhibition is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as amnesia and anxiety suppression in a manner which can further decrease the person's observance of and regard for social norms. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of GABAergic depressants, such as alcohol,[226] benzodiazepines,[227] phenibut, and GHB. However, it may also occur under the influence of certain stimulants,[228] entactogens,[229] and dissociatives[230].

Dream suppression

Dream suppression is defined as a decrease in the vividness, intensity, frequency, and recollection of a person's dreams. At its lower levels, this can be a partial suppression which results in the person having dreams of a lesser intensity and a lower rate of frequency. However, at its higher levels, this can be a complete suppression which results in the person not experiencing any dreams at all.

Dream suppression is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of cannabinoids[231] and most types of antidepressants[232][233][234]. This is due to the way in which they increase REM latency, decrease REM sleep, reduce total sleep time and efficiency, and increase wakefulness.[231][232][233][235] REM sleep is where the majority of dreams occur.[236]

Emotion suppression

Emotion suppression (also known as flat affect, apathy, or emotional blunting) is medically recognized as a flattening or decrease in the intensity of one's current emotional state below normal levels.[237][238][239] This dulls or suppresses the genuine emotions that a person was already feeling prior to ingesting the drug. For example, an individual who is currently feeling somewhat anxious or emotionally unstable may begin to feel very apathetic, neutral, uncaring, and emotionally blank. This also impacts the degree to which the person will express their emotional state through body language, tone of voice, and facial expressions.

It is worth noting that although a reduction in the intensity of one's emotions may be beneficial at times (e.g., the blunting of an anger response in a volatile patient), it may be detrimental at other times (e.g., emotional indifference at the funeral of a close family member).[240]

Emotion suppression is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as motivation suppression, thought deceleration, and analysis suppression. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of antipsychotic compounds, such as quetiapine, haloperidol, and risperidone.[237][122] However, it can also occur in less consistent form under the influence of heavy dosages of dissociatives,[241][242] SSRI's,[240][124] and GABAergic depressants[243].

Focus suppression

Focus suppression (also known as distractability[244]) is medically recognized as a decreased ability to selectively concentrate on an aspect of the environment while ignoring other things.[245][246] It can be best characterized by feelings of intense distractability which can prevent one from focusing on and performing basic tasks that would usually be relatively easy to not get distracted from.[247] This effect will often synergize with other coinciding effects such as motivation suppression, thought deceleration, and sedation.[21]

Focus suppression is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as sedation, motivation suppression, and creativity suppression. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate or heavy dosages of antipsychotics,[248] benzodiazepines, cannabinoids,[21] and hallucinogens. However, it is worth noting that stimulant compounds which primarily induce focus enhancement at light to moderate dosages will also often lead into focus suppression at their heavier dosages.[176]

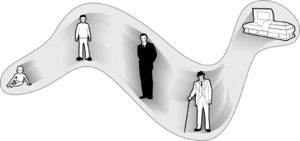

Memory suppression

Memory suppression (also known as ego suppression, ego dissolution, ego loss or ego death) is defined as an inhibition of a person's ability to maintain a functional short and long-term memory.[249][188][70] This occurs in a manner that is directly proportional to the dosage consumed, and often begins with the degradation of one's short-term memory.

Memory suppression is a process which may be broken down into the 4 basic levels described below:

- Partial short-term memory suppression - At the lowest level, this effect is a partial and potentially inconsistent failure of a person's short-term memory. It can cause effects such as a general difficulty staying focused, an increase in distractibility, and a general tendency to forget what one is thinking or saying.

- Complete short-term memory suppression - At this level, this effect is the complete failure of a person's short-term memory. It can be described as the experience of being completely incapable of remembering any specific details regarding the present situation and the events leading up to it for more than a few seconds. This state of mind can often result in thought loops, confusion, disorientation, and a loss of control, especially for the inexperienced. At this level, it can also become impossible to follow both conversations and the plot of most forms of media.

- Partial long-term memory suppression - At this level, this effect is the partial, often intermittent failure of a person's long-term memory in addition to the complete failure of their short-term memory. It can be described as the experience of an increased difficulty recalling basic concepts and autobiographical information from one's long-term memory. Compounded with the complete suppression of short term memory, it creates an altered state where even basic tasks become challenging or impossible as one cannot mentally access past memories of how to complete them.

For example, one may take a longer time to recall the identity of close friends or temporarily forget how to perform basic tasks. This state may create the sensation of experiencing something for the first time. At this stage, a reduction of certain learned personality traits, awareness of cultural norms, and linguistic recall may accompany the suppression of long-term memory.

- Complete long-term memory suppression - At the highest level, this effect is the complete and persistent failure of both a person's long and short-term memory. It can be described as the experience of becoming completely incapable of remembering even the most basic fundamental concepts stored within the person's long-term memory. This includes everything from their name, hometown, past memories, the awareness of being on drugs, what drugs even are, what human beings are, what life is, that time exists, what anything is, or that anything exists.

Memory suppression of this level blocks all mental associations, attached meaning, acquired preferences, and value judgements one may have towards the external world. Sufficiently intense memory loss is also associated with the loss of a sense of self, in which one is no longer aware of their own existence. In this state, the user is unable to recall all learned conceptual knowledge about themselves and the external world, and no longer experiences the sensation of being a separate observer in an external world. This experience is commonly referred to as "ego death".

Memory suppression is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as thought loops, personal bias suppression, amnesia, and delusions. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics, dissociatives, and deliriants.[250]

It is worth noting that although memory suppression is vaguely similar in its effects to amnesia, it differs in that it directly suppresses one's usage of their long or short term memory without inhibiting the person's ability to recall what happened during this experience afterward. In contrast, amnesia does not directly affect the usage of one's short or long-term memory during its experience but instead renders a person incapable of recalling events after it has worn off. A person experiencing memory suppression cannot access their existing memory, while a person with drug-induced amnesia cannot properly store new memories. As such, a person experiencing amnesia may not obviously appear to be doing so, as they can often carry on normal conversations and perform complex tasks. This is not the case with memory suppression.

Personal bias suppression

Personal bias suppression (also called cultural filter suppression) is defined as a decrease in the personal or cultural biases, preferences, and associations which a person knowingly or unknowingly filters and interprets their perception of the world through.[251]

Analyzing one's beliefs, preferences, or associations while experiencing personal bias suppression can lead to new perspectives that one could not reach while sober. The suppression of this innate tendency often induces the realization that certain aspects of a person's personality, world view and culture are not reflective of objective truths about reality, but are in fact subjective or even delusional opinions.[251] This realization often leads to or accompanies deep states of insight and critical introspection which can create significant alterations in a person's perspective that last anywhere from days, weeks, months, or even years after the experience itself.

Personal bias suppression is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as conceptual thinking, analysis enhancement, and especially memory suppression. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of hallucinogens such as dissociatives and psychedelics. However, it can also occur to a much lesser extent under the influence of very heavy dosages entactogens and cannabinoids.

Sleepiness

Sleepiness (also known as drowsiness) is medically recognized as a state of near-sleep, or a strong desire for sleep without feeling a decrease in one's physical energy levels.[252][253][254] This state is independent of a circadian rhythm;[252] so, unlike sedation, this effect does not necessarily decrease physical energy levels but instead decreases wakefulness. It results in a propensity for tired, clouded, and sleep-prone behaviour. This can lead into a decreased motivation to perform tasks, as the increase in one's desire to sleep begins to outweigh other considerations. Prolonged exposure to this effect without appropriate rest can lead to cognitive fatigue and a range of other cognitive suppressions.

Sleepiness is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of a wide variety of compounds such as cannabinoids,[255] GABAergic depressants,[256][257] opioids,[258] antipsychotics,[259][135] some antihistamines,[260] and certain psychedelics. However, it is worth noting that the few compounds which selectively induce this effect without a number of other accompanying effects are referred to as hypnotics.

Suggestibility suppression

Suggestibility suppression is defined as a decreased tendency to accept and act on the suggestions of others. A common example of suggestibility suppression in action would be a person being unwilling to believe or trust another person's suggestions without a greater amount of prior discussion than would usually be considered necessary during every day sobriety.

Although this effect can occur as a distinct mindstate, it may also arise due to interactions between a number of other effects. For example, a person who is currently experiencing mild paranoia combined with analysis enhancement may find themselves less trusting and more inclined to think through the suggestions of others before acting upon them, alternatively, a person who is experiencing ego inflation may find that they value their own opinion over others and are therefore equally less likely to follow the suggestions of others.

Alcohol has been shown to decrease suggestibility in a dose-dependent manner,[261][262] while its withdrawals increases suggestibility.[263] A large proportion of individuals who come in contact with law enforcement personnel are under the influence of alcohol, including perpetrators, victims, and witnesses of crimes. This has to be taken into account when investigative interviews are planned and conducted, and when the reliability of the information derived from such interviews is evaluated.[261][262][263]

Suggestibility suppression is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as irritability[261] and ego inflation. It is most commonly induced under the influence of GABAergic depressants.[261][262][263]

Thought deceleration

Thought deceleration (also known as bradyphrenia)[264] is defined as the process of thought being slowed down significantly in comparison to that of normal sobriety. When experiencing this effect, it will feel as if the time it takes to think a thought and the amount of time which occurs between each thought has been slowed down to the point of greatly impairing cognitive processes. It can manifest itself in delayed recognition, slower reaction times, and fine motor skills deficits.

Thought deceleration is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as analysis suppression and sedation in a manner which not only decreases the person's speed of thought, but also significantly decreases the sharpness of a person's mental clarity. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of depressant compounds, such as GABAergics,[265][266][267] antipsychotics,[268] and opioids.[269][270][271] However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of heavy dosages of hallucinogens such as psychedelics,[32] dissociatives,[272] deliriants,[267][273] and cannabinoids.[274][275][276][277]

Novel cognitive states

A novel cognitive state is defined as any cognitive effect which does not merely amplify or suppress familiar states of mind, but rather induces an experience that is qualitatively different from that of ordinary consciousness.

Although many transpersonal and psychological effects also technically fit into this definition, they are excluded from this category of effects as they have their own defining qualities which standard novel states do not.

This page lists and describes the various novel states which can occur under the influence of certain psychoactive compounds.

Cognitive dysphoria

Cognitive dysphoria (semantically the opposite of euphoria) is medically recognized as a cognitive and emotional state in which a person experiences intense feelings of dissatisfaction, and in some cases indifference to the world around them.[278][279] These feelings can vary in their intensity depending on the dosage consumed and the user's susceptibility to mental instability. Although dysphoria is an effect, the term is also used colloquially to define a state of general melancholic unhappiness (such as that of mild depression)[280][281] often combined with an overwhelming sense of discomfort and malaise.[282]

Cognitive dysphoria is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as anxiety and depression.[278][279][283] It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of deliriant compounds, such as DPH and datura. However, it can also occur during a stimulant's offset and during the withdrawal symptoms of almost any substance.

Cognitive euphoria

Cognitive euphoria (semantically the opposite of cognitive dysphoria) is medically recognized as a cognitive and emotional state in which a person experiences intense feelings of well-being, elation, happiness, excitement, and joy.[284] Although euphoria is an effect (i.e. a substance is euphorigenic),[285][286] the term is also used colloquially to define a state of transcendent happiness combined with an intense sense of contentment.[287] However, recent psychological research suggests euphoria can largely contribute to but should not be equated with happiness.[288]

Cognitive euphoria is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as physical euphoria and tactile intensification. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of opioids, entactogens, stimulants, and GABAergic depressants. However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of hallucinogenic compounds such as psychedelics, dissociatives, and cannabinoids.

Compulsive redosing

Compulsive redosing is defined as the experience of a powerful and difficult to resist urge to continuously redose a psychoactive substance in an effort to increase or maintain the subjective effects which it induces.[289][290][291][292]

This effect is considerably more likely to manifest itself when the user has a large supply of the given substance within their possession. It can be partially avoided by pre-weighing dosages, not keeping the remaining material within sight, exerting self-control, and giving the compound to a trusted individual to keep until they deem it safe to return.

Compulsive redosing is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as cognitive euphoria, physical euphoria, or anxiety suppression alongside of other effects which inhibit the clarity of one's decision-making processes such as disinhibition, motivation enhancement, and ego inflation. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of a wide variety of compounds, such as opioids, stimulants,[290][292][293] GABAergics,[290] and entactogens.[291] However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of dissociatives and cannabinoids.[291]

Conceptual thinking

Conceptual thinking is defined as an alteration to the nature and content of one's internal thought stream. This alteration predisposes a user to think thoughts which are no longer primarily comprised of words and linear sentence structures. Instead, thoughts become equally comprised of what is perceived to be incredibly detailed renditions of the innately understandable and internally stored concepts for which no words exist. Thoughts cease to be spoken by an internal narrator and are instead “felt” and intuitively understood.

For example, if a person was to think of an idea such as a "chair" during this state, one would not hear the word as part of an internal thought stream, but would feel the internally stored, pre-linguistic and innately understandable data which comprises the specific concept labelled within one's memory as a "chair". These conceptual thoughts are felt in a comprehensive level of detail that feels as if it is unparalleled within the primarily linguistic thought structure of everyday life. This is sometimes interpreted by those who undergo it as some "higher level of understanding".

During this experience, conceptual thinking can cause one to feel not just the entirety of a concept's attributed data, but also how a given concept relates to and depends upon other known concepts. This can result in the perception that the person can better comprehend the complex interplay between the idea that is being contemplated and how it relates to other ideas.

Conceptual thinking is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as personal bias suppression and analysis enhancement. It is most commonly induced under the influence of moderate dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics and dissociatives. However, it can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of entactogens, cannabinoids, and meditation.

Multiple thought streams

Multiple thought streams is defined as a state of mind in which a person has more than one internal narrative or stream of consciousness simultaneously occurring within their head. This can result in any number of independent thought streams occurring at the same time, each of which are often controllable in a similar manner to that of one's everyday thought stream.

These multiple coinciding thought streams can be experienced simultaneously in a manner which is evenly distributed and does not prioritize the awareness of any particular thought stream over an other. However, they can also be experienced in a manner which feels as if it brings awareness of a particular thought stream to the foreground while the others continue processing information in the background. This form of multiple thought streams typically swaps between specific trains of thought at seemingly random intervals.

The experience of this effect can sometimes allow one to analyze many different ideas simultaneously and can be a source of great insight. However, it will usually overwhelm the person with an abundance of information that becomes difficult or impossible to fully process at a normal speed.

Multiple thought streams are often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as memory suppression and thought disorganization. They are most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of psychedelic compounds, such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline.

Simultaneous emotions

Simultaneous emotions is defined as the experience of feeling multiple emotions simultaneously without an obvious external trigger. For example, during this state a user may suddenly feel intense conflicting emotions such as simultaneous happiness, sadness, love, hate, etc. This can result in states of mind in which the user can potentially feel any number of conflicting emotions in any possible combination.

Simultaneous emotions are often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as memory suppression and emotion intensification. They are most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of psychedelic compounds, such as LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline.

Thought loops

A thought loop is defined as the experience of becoming trapped within a chain of thoughts, actions and emotions which repeats itself over and over again in a cyclic loop. These loops usually range from anywhere between 5 seconds and 2 minutes in length. However, some users have reported them to be up to a few hours in length. It can be extremely disorientating to undergo this effect and it often triggers states of progressive anxiety within people who may be unfamiliar with the experience. The most effective way to end a cycle of thought loops is to simply sit down and try to let go.

This state of mind is most likely to occur during states of memory suppression in which there is a partial or complete failure of the person's short-term memory. This may suggest that thought loops are the result of cognitive processes becoming unable to sustain themselves for appropriate lengths of time due to a lapse in short-term memory, resulting in the thought process attempting to restart from the beginning only to fall short once again in a perpetual cycle.

Thought loops are most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds,[7] such as psychedelics and dissociatives. However, they can also occur to a lesser extent under the influence of extremely heavy dosages of stimulants and benzodiazepines.

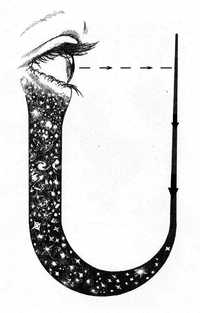

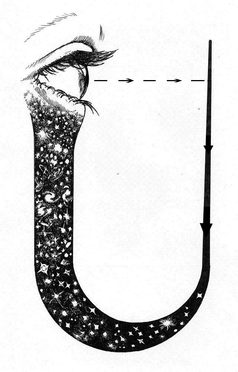

Time distortion

Time distortion is defined as an effect that makes the passage of time feel difficult to keep track of and wildly distorted.[294] It is usually felt in two different forms, time dilation and time compression.[31] These two forms are described and documented below:

Time dilation

Time dilation is defined as the feeling that time has slowed down.[295] This commonly occurs during intense hallucinogenic experiences and seems to stem from the fact that during an intense trip, abnormally large amounts of experience are felt in very short periods of time.[296][297] This can create the illusion that more time has passed than actually has. For example, at the end of certain experiences, one may feel that they have subjectively undergone days, weeks, months, years, or even infinite periods of time.

Time dilation is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as spirituality intensification,[298] thought loops, novelty enhancement, and internal hallucinations in a manner which may lead one into perceiving a disproportionately large number of events considering the amount of time that has actually passed in the real world. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics,[299][300] dissociatives, entactogens,[301][302] and cannabinoids.

Time compression

Time compression is defined as the experience of time speeding up and passing much quicker than it usually would while sober. For example, during this state a person may realize that an entire evening has passed them by in what feels like only a couple of hours.

This commonly occurs under the influence of certain stimulating compounds and seems to at least partially stem from the fact that during intense levels of stimulation, people typically become hyper-focused on activities and tasks in a manner which can allow time to pass them by without realizing it. However, the same experience can also occur on depressant compounds which induce amnesia. This occurs due to the way in which a person can literally forget everything that has happened while still experiencing the effects of the substance, thus giving the impression that they have suddenly jumped forward in time.

Time compression is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as memory suppression, focus intensification, stimulation, and amnesia in a manner which may lead one into perceiving a disproportionately small number of events considering the amount of time that has actually passed in the real world. It is most commonly induced under the influence of heavy dosages of stimulating and/or amnesic compounds,[303] such as dissociatives,[304] entactogens, amphetamines, and benzodiazepines.

Time reversal

Time reversal is defined as the perception that the events, hallucinations, and experiences that occurred around one's self within the previous several minutes to several hours are spontaneously playing backwards in a manner which is somewhat similar to that of a rewinding VHS tape. During this reversal, the person's cognition and train of thought will typically continue to play forward in a coherent and linear manner while they watch the external environment around them and their body's physical actions play in reverse order. This can either occur in real time, with 5 minutes of time reversal taking approximately 5 minutes to fully rewind, or it can occur in a manner which is sped up, with 5 minutes of time reversal only taking less than a minute. It can reasonably be speculated that the experience of time reversal may potentially occur through a combination of internal hallucinations and errors in memory encoding.

Time reversal is often accompanied by other coinciding effects such as internal hallucinations, thought loops, and deja vu. It is most commonly induced under the influence of extremely heavy dosages of hallucinogenic compounds, such as psychedelics, dissociatives, and deliriants.

Psychological effects

Psychological effects are defined as any cognitive effect that is either established within the psychological literature or arises as a result of the complex interplay between other more simplistic components such as cognitive enhancements, intensifications, and suppressions.

This page lists and describes the various psychological effects which can occur under the influence of certain psychoactive compounds.

Catharsis