Routes of administration

A route of administration is the method in which a psychoactive substance is delivered into the body.

The route through which a substance is administered can greatly impact its potency, duration, and subjective effects. For example, many substances are more effective when consumed using particular routes of administration, while some substances are completely inactive with certain routes.

Determining an optimal route of administration is highly dependent on the substance consumed, its desired duration and potency and side effects, and one's personal comfort level.

Intravenous injection is the fastest route of administration, causing blood concentrations to rise the most quickly, followed by smoking, suppository (anal or vaginal insertion), insufflation (snorting), and ingestion (swallowing).[1] A rapid rise in concentration can trigger an intense surge of effects for many substances. A rapid rise in concentration can trigger a quick rush of effects for many substances.

Multi-route hazard substances

Orally inactive tryptamines

- Substances: 5-MeO-DMT, DMT.

- Routes of administration:

- Oral: When these substances are taken orally, they are inactive because stomach enzymes called MAO enzymes break it down. To experience effects orally, they are frequently combined with MAO inhibitors (MAOIs), which prevent this breakdown. This combination is known as pharmahuasca for DMT (or 5-MeO-DMT). When the MAOIs and DMT are derived from plant extracts, it is referred to as ayahuasca. However, it is important to note that MAOIs require careful consideration, as they can be dangerous when combined with certain drug classes, potentially leading to life-threatening consequences if not used properly.

- Orally ingested as unintended second route: Any amount swallowed undergoes rapid enzymatic degradation in the stomach, rendering it inactive. This can introduce variability in effect intensity among users. Inconclusive experiences due to the swallowed substance may lead to a false sense of security, potentially causing users to increase the dose in subsequent administrations. However, due to the unpredictable nature of salivation or intranasal dripping, this could result in an unexpectedly potent dose due to less substance being metabolized in the stomach.

- In the mouth (buccal (sublabial), sublingual): Holding the substances in the mouth can increase salivation, causing it to be swallowed and deactivated by stomach enzymes. Additionally, many alkaloids, have a bitter taste that makes them difficult to keep in the mouth, triggering a swallowing reflex. To improve tolerability with this route, using a safe taste-masking agent is recommended.

- Insufflation (snorting): When these substances are delivered intranasally (through the nose), they can deposit along the nasal passage and drip down into the gastrointestinal tract.

Oral cavity

It is worth noting that most substances are reported to be strongly bitter and unpleasant to administer via sublingual or buccal routes.

Oral

Oral administration is the most common route of administration for most substance classes. This route allows a substance to be absorbed through blood vessels lining the stomach and intestines. The onset is generally slower than other methods of ingestion as it must undergo first-pass metabolism through the liver (may vary greatly between individual substances).[2] Additionally, the absorption and overall duration are generally longer as well.

Risks

This method can also have a greater propensity for nausea and gastrointestinal discomfort.[3][4]

25I-NBOMe is widely rumored to be orally inactive; however, apparent overdoses have occurred via oral administration.

Oral mucosa

Buccal

Buccal administration refers to absorption through the cheek and gum.

This route is commonly employed when ingesting potent psychedelics such as 25I-NBOMe, DOM, LSD, and other substances distributed on blotter paper. Potent clandestine manufactured benzodiazepines like alprazolam and etizolam are also sometimes distributed on blotters.

Like sublingual absorption, the substance is largely absorbed through the lingual artery, but is also absorbed through the gum lining. This method is used when chewing plant leaves such as khat, kratom, salvia divinorum, and sometimes tobacco (snus).

Sublingual

Sublingual administration refers to absorption under the tongue.[5] It is a common route of administration for lysergamides like LSD.

This route causes the substance to be absorbed through the large lingual artery present underneath the tongue, generally resulting in a faster absorption than oral administration.

It also circumvents first-pass metabolism of certain substances which can be absorbed via sublingual and buccal administration but not oral administration (e.g. 25x-NBOMe, 25x-NBOH).

Risks

Caustic compounds, such as the freebase form of amine-containing substance, should not be used sublingually because they can severely burn the inside of one's mouth.

Nasal cavity

SARS-CoV-2: drug use safety considerations

Avoid sharing drug paraphernalina for insufflation (straws, bank notes, ‘Kuripe’, etc).

Nasal spray

"The administration of nasal powder formulations has been associated with greater sensory irritation than liquid sprays and the amount of powder.".[6]

To learn how to make nasal spray, see the nasal spray guide.

Insufflation

Chinese snuff bottle stopper with a snuff spoon (also known as a cocaine spoon)

Ketamine prepared in a spiral for "snorting". A common technique for self-administration of some recreational drugs.

Lines of cocaine prepared for snorting

Insufflation (also called "inhalation" and "snorting") refers to the introduction of a substance into the sinus via the nostrils, circumventing first pass metabolism.

It is a very common method of use for substances in powder form, specifically so-called "street drugs" like cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine. Some users find this route to be painful and uncomfortable, although certain substances are easier to insufflate than others.

This method is capable of rapid absorption through mucous membranes and blood vessels in the sinus. Absorption and onset is generally much more rapid than oral and, as a result, a substance feels much more intense and is often shorter acting than if taken orally.

Insufflation is common with substances such as cocaine and ketamine. It is also utilized in yopo rituals, the self-applicator pipe is known as ‘Kuripe’, and the blow pipe is known as a ‘Tepi’ in the Brazilian tradition. Insufflating tobacco in snuff form was a common practice until the early 20th century.[citation needed]

Risks

Warning: Nasal Administration Insufflation can cause nasal damage, bleeding, and—with repeated long-term use—irreversible damage to the nose and surrounding tissues. Sharing snorting equipment (including banknotes) increases the risk of transmitting blood-borne diseases (such as hepatitis C and HIV). To stay safer: Prepare substances into a fine powder before use, and always use your own clean snorting tool. Limit how much you use in each nostril per session, and rinse your nose with saline within 30–60 minutes after use (after the peak effects) to clear out any leftover material and reduce irritation. If with others, don’t let anyone push you to use. Alternatively: Buccal administration may be used as a harm reduction option. This involves placing the powder (for example, wrapped in a small piece of toilet paper) under the lip, allowing it to absorb through the cheek or gum. This method avoids nasal damage, though it may have different effects and risks, such as irritation to the mouth or gums. Learn more about nasal administration risks. |

Short-term side effects of insufflation includes nasal congestion, which may last for 24 hours.

Frequent insufflation of some substances can damage one's mucous membranes, induce bleeding, damage the nostril's cartilage and lining, burn the throat, and cause other trauma to the nasal passage and sinus area.[7] A nasal septum perforation is a medical condition in which the nasal septum, the bony/cartilaginous wall dividing the nasal cavities, develops a hole or fissure.

Also, sharing snorting equipment (nasal spray bottles, straws, banknotes, bullets, etc) has been linked to the transmission of hepatitis C. (Bonkovsky and Mehta) In one study, the University of Tennessee Medical Center researches warned that other blood-borne diseases such as HIV, the AIDS-causing virus, could be transmitted as well.[8] Drinking makes it harder to resist pressure and clouds your ability to make safe choices. Not only might you miss signs of danger, like blood stains on shared equipment, but alcohol weakens your immune system, making it easier to catch and spread viruses.

Respiratory tract

SARS-CoV-2: drug use safety considerations

Avoid sharing drug paraphernalina for inhalation (vapes, joints, pipes, etc).

Inhalants

Inhalants can be delivered through the respiratory system in two main ways:

- Mouth inhalation: This method involves breathing in a gas or vapor through the mouth. Nitrous oxide is a common example.

- Nasal inhalation: This method involves breathing in a gas, vapor, or volatile liquid through the nose. Volatile viscous compounds like poppers are typically inhaled this way.

Inhalants do not require an external heat source to produce psychoactive vapors that can then be inhaled through various methods depending on the substance used. Inhaled substances are absorbed very rapidly and lead to an almost instantaneous absorption of the substance and passage through the blood brain barrier.[9]

Risks

It is substantially easier to overdose on alcohol inhalation than drinking alcohol.

Many substances can be inhaled to achieve an altered state of consciousness, however, some substances used for this purpose produce highly negative physical and neurotoxic effects including solvents like toluene (see toluene toxicity) often found in glue, acetone often found in nail polish, and gasoline.[10], and number of gases intended for household or industrial use including butane gas sold as lighter gas refill.

Inhaling liquified gas directly from cans or canisters can freeze the throat.

Heating

Substances that come in HCl form can be converted to freebase by mean of pH regulation. For example, cocaine decomposes when heated strongly so the freebase and hydrogen carbonate salts of cocaine, which have much lower boiling points compared to the hydrochloride salt, are typically used when the substance is to be vaporized and are known as cocaine base and "crack" respectively.

Other substances decomposes to easily even from low heat so they cannot even be vaporized for this reason. Examples of substances include amphetamine, caffeine, LSD, and psilocybin. Also, there's not a single trip report in PiHKAL (“Phenethylamines I Have Known and Loved”) in which the subject is smoking or vaporizing the phenethylamine compound. Notable compunds in PiHKAL include MDMA, and the “Magical half-dozen” (mescaline, DOM, 2C-B, 2C-E, 2C-T-2, 2C-T-7). However, a substituted phenethylamine that was synthesized after PiHKAL was released albeit very toxic, 25I-NBOMe, has been smoked.[11]

Smoked

Smoking substances is a common method of consumption with the most common examples including cannabis and tobacco. Smoking yeilds low bioavailability, especially if the substance is smoked slowly.

To smoke a substance a direct heat source, most often a flame, is applied directly to the substance with no barrier between the heat source and the substance. The smoking of substances can lead to an almost instantaneous absorption of the substance and passage through the blood brain barrier.[2]

When a substance is smoked, the substance is absorbed through blood vessels found in the bronchi tubes contained within the lungs. Like insufflation, the duration is decreased while its intensity is increased in proportion to oral absorption.

Cannabis is commonly consumed via the respiratory tract. The average THC transfer rate for joints, bongs, and vaporizers, is 20-26%,[12] 40%,[12] and 55-83%,[13] respectively. For a proper gas or smoke deposition, one are advised to take a deep initial breath, and then hold it for 10 seconds to allow for the gas or smoke to get fully absorbed in the lungs (Which is not the case). Subjects are frequently instructed to follow the "10 seconds rule" in studies.[14][15] Prolonged breath holding does not substantially enhance the effects of inhaled marijuana smoke.[16][17]

Bongs that are cleaned regularly eliminates yeast, fungi, bacteria and pathogens that can cause several symptoms that vary from allergy to lung infection.[18][19][20]

Gravity bong

Spots

Spots (also known as spotting, knifers, knife hits, knife tokes, dots, hot knives, kitchen tracking blades, or bladers) refers to a method of smoking cannabis.[21] Small pieces of cannabis are rolled (or simply torn from a larger bud) to form the spot.

Risk

Users spotting cannabis are susceptible to greater health risks than other methods of smoking cannabis. Spotting cannabis oil or resin is thought to be particularly harmful to the lungs, as the smoke comes off the oil at such a high temperature.[22]

Vaporized

Vaporizing substances is a common method of consumption with the most common examples including cannabis and nicotine, but also heroin and crack-cocaine. Vaporizing a substance, especially with a digital temperature controlled device, allows for more temperature control because the flame or heat source does not come into direct contact with the substance.

Even though many drugs, like heroin and oxycodone pills are colloquially referred to as "smoked" the process used to consume them is vaporization. Vaporizing substances can lead to an almost instantaneous absorption of the substance and passage through the blood brain barrier.[2]

When a substance is vaporized, the substance is absorbed through blood vessels found in the bronchi tubes contained within the lungs. Like insufflation, the duration is decreased while its intensity is increased in proportion to oral absorption.

Vaporization is commonly associated with the vaporizer pens that have become popular within the past decade, but it is not limited to ingesting the vapors from an electronic heat source.

Risks

Smoking a substance that should be vaporized leads to a blast of heat that may burn off the active ingredient or ignite the substance itself, both of which are wasteful and incorrect, which may cause judgement impairment of the dosage.

Ethnobotanist Daniel Siebert cautions that inhaling hot air can be irritating and potentially damaging to the lungs. Vapor produced by a heat gun needs to be cooled by running it through a water pipe or cooling chamber before inhalation.[23]

Re-used uncleaned vapes, and vape sharing, may cause bacterial pneumonia,[24][25] fungal pneumonia,[26] and viral pneumonia.[24]

E-cigarette

An electronic cigarette is an electronic device that simulates tobacco smoking. It consists of an atomizer, a power source such as a battery, and a container such as a cartridge or tank. Instead of smoke, the user inhales vapor. As such, using an e-cigarette is often called "vaping". The atomizer is a heating element that vaporizes a liquid solution called e-liquid. The most common e-liquid carrying agents includes glycerin (often called vegetable glycerin, or VG), and propylene glycol (often referred to as PG).

Risks

Vaping-associated pulmonary injury (VAPI) is an umbrella term used to describe lung diseases associated with the use of vaping products that can be severe and life-threatening.

Glycerin was long thought to be a safe option. However, the carcinogen formaldehyde is known as a product of propylene glycol and glycerol vapor degradation.[27]

The Machine

The Machine, utilizing a glass bottle with a hole, and foil in the neck. The Machine was invented to make it more convenient to smoke DMT, but it can be used for any substance.

Chasing the dragon

Heroin is colloquially referred to as "smoked" but is really vaporized, often using tinfoil as a barrier between the substance and the flame source. The heat source can be held at different distances as temperature control. An alternative version is to use a "stainless steel one-quarter teaspoon and vaporized it over a cigarette lighter collecting the smoke in an upside-down funnel."[28]

Risks

Overdosing from inhaling vaporized drugs through the "chasing the dragon" method is extremely difficult to anticipate. This technique does not allow for a controlled, standardized dose. Even experienced users cannot accurately gauge how much of the substance has been vaporized, burned, and ultimately inhaled into the body.

The inconsistent and unregulated nature of this consumption method creates a false sense of safety. A dose that seemed harmless one time may potentially prove fatal the next, as various random factors influence how much of the drug is actually ingested.

Moreover, using specialized smoking devices like bongs designed for more efficient inhalation dramatically increases the amount consumed compared to rudimentary foil methods. An amount that may have been tolerable when smoked off foil could easily become an overdose when the same quantity is fully vaporized and inhaled through an optimized apparatus.

The lack of dosage control and potential to underestimate potency make chasing the dragon an inherently risky and unpredictable way to use drugs, with an ever-present danger of accidental overdose.

#The Machine is a much safer than "chasing the dragon".

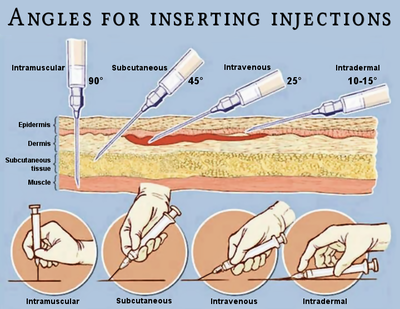

Injection

Some drugs should not be taken by injection: For example, injectable codeine is available for subcutaneous or intramuscular injection only; intravenous injection is contraindicated as this can result in non-immune mast-cell degranulation and resulting anaphylactoid reaction.

About 0.1 mL of the solution is lost in conventional syringes through the Luer taper tip and the Luer taper adapter of the hypodermic needle. That can be compensated by either adding extra 10% or 5% substance in 1 mL or 2 mL syringes respectively, or by using low dead space syringes.

Intravenous

Intravenous administration refers to a drug being directly introduced into the bloodstream using a hypodermic needle. This method has the benefit of a very short onset and eliminates absorption by directly entering the bloodstream.[2] However, much greater care must be taken when compared to other methods of administration.

Sterilized, unused needles and a high purity substance with little to no adulterant are required to avoid damage to the circulatory system.[29]

Make sure no air bubbles are present in the reservoir before the plunger is released. Hold the syringe vertically and flick it with your fingers to release bubbles to the needle adapter, and gently push the plunger. Don't worry about air embolism, it is estimated that a large volume of 50-500 mL or greater infused at a rapid rate is potentially fatal.[30][31]

This route is strongly associated with substances that have bad oral bioavailability, such as heroin and cocaine, but can be employed with almost any pure substance.

Intramuscular

Intramuscular administration refers to a drug being injected into the muscle tissue using a hypodermic needle. This method is very similar to the intravenous route, but is often more painful with a decreased onset and absorption. Some drugs (such as ketamine that has low oral bioavailability, and is dangerous to take intravenously rapidly) are commonly administered via this route.[32] Like intravenous administration, intramuscular injection must be taken with precaution, using sterilized unused needles.

Subcutaneous

Subcutaneous administration (also known as skin popping) refers to a drug being injected into the subcutis, the layer of skin directly below the dermis and epidermis. Subcutaneous administration is relatively uncommon among psychonautics, as many people are not trained how to do it or would rather use a different route of administration which they are more familiar with.

Rectal

Rectal administration, also commonly referred to as boofing or plugging, is one of the most effective methods of administration for many substances.[33][5] The absorption rate is very high compared to other methods and the onset is usually very short, generally with a higher intensity and shorter duration.

This is due to a large amount of arteries located in the rectum; thus rectal administration is often superior to other methods despite social stigma.

Rectal administration can involve either the insertion of a low-volume solution into the rectum, using a syringe or pipette, or by placing a pill or gelatin capsule containing the active substance. The latter form is known as a suppository, and is common in medicine when the gastrointestinal tract cannot support oral medicine.

Risks

Caustic substances such as 4-FA or phenibut hydrochloride should not be plugged because they can burn the interior rectum resulting in a considerable amount of gastrointestinal distress.

Transdermal

Transdermal administration delivers active ingredients through the skin for systemic effects throughout the body. This method is used in various medications, including:

- Transdermal patches: These deliver controlled doses of some stimulant like nicotine patches, and caffeine patches. Patches for opioids such as fentanyl also exist.[34]

- Transdermal implants: Used for medical or anesthetic purposes.

This route is typically not observed in non-medical or recreational contexts due to the manufacturing requirements.

Ocular

- Transconjunctival: Most commonly observed medically (ex. eyedrops) but infrequently occurs with recreational drug abuse, such as with LSD and Heroin

- Intraocular: This route is rarely observed in non-ophthalmological-medical or recreational environments due to the fragile and complex structure of the eye

Risks

Transconjunctival drug administration has been associated with corneal and conjunctival abrasions and hemorrhaging[35]

See also

External links

References

- ↑ Goeders, Nicholas E. (2017). "Intravenous and smoked methamphetamine produce different subjective and physiological effects in women". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 171: e73. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.08.210.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Ohlsson, A., Lindgren, J.-E., Wahlen, A., Agurell, S., Hollister, L. E., Gillespie, H. K. (September 1980). "Plasma delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol concentrations and clinical effects after oral and intravenous administration and smoking". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 28 (3): 409–416. doi:10.1038/clpt.1980.181. ISSN 0009-9236.

- ↑ Niv, D., Davidovich, S., Geller, E., Urca, G. (December 1988). "Analgesic and hyperalgesic effects of midazolam: dependence on route of administration". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 67 (12): 1169–1173. ISSN 0003-2999.

- ↑ Porter, W. R., Intraoral methods of using benzodiazepines

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 De Boer, A. G., De Leede, L. G. J., Breimer, D. D. (January 1984). "DRUG ABSORPTION BY SUBLINGUAL AND RECTAL ROUTES". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 56 (1): 69–82. doi:10.1093/bja/56.1.69. ISSN 0007-0912.

- ↑ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35386013/

- ↑ Ask Erowid : ID 41 : Is snorting MDMA worse for you than taking it orally?

- ↑ Sharing Drug “Snorting Straws” Spreads Hepatitis C, 2016

- ↑ http://www.ct.gov/dds/lib/dds/edsupp/medadmin_recert_part_ii.pdf

- ↑ Burbacher, T. M. (December 1993). "Neurotoxic effects of gasoline and gasoline constituents". Environmental Health Perspectives. 101 (Suppl 6): 133–141. ISSN 0091-6765.

- ↑ "2C-I-NBOMe (25I) Effects". Erowid.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 https://www.ukcia.org/research/FactorsThatInfluenceBioavailability.pdf

- ↑ Lanz, C., Mattsson, J., Soydaner, U., Brenneisen, R. (19 January 2016). "Medicinal Cannabis: In Vitro Validation of Vaporizers for the Smoke-Free Inhalation of Cannabis". PLoS ONE. 11 (1): e0147286. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0147286. ISSN 1932-6203.

- ↑ Wallace, M. S., Marcotte, T. D., Umlauf, A., Gouaux, B., Atkinson, J. H. (July 2015). "Efficacy of Inhaled Cannabis on Painful Diabetic Neuropathy". The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 16 (7): 616–627. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2015.03.008. ISSN 1526-5900.

- ↑ Wilsey, B., Marcotte, T., Tsodikov, A., Millman, J., Bentley, H., Gouaux, B., Fishman, S. (June 2008). "A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Trial of Cannabis Cigarettes in Neuropathic Pain". The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 9 (6): 506–521. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2007.12.010. ISSN 1526-5900.

- ↑ Zacny, J. P., Chait, L. D. (1991). "Response to marijuana as a function of potency and breathhold duration". Psychopharmacology. 103 (2): 223–226. doi:10.1007/BF02244207. ISSN 0033-3158.

- ↑ Zacny, J. P., Chait, L. D. (June 1989). "Breathhold duration and response to marijuana smoke". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 33 (2): 481–484. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(89)90534-0. ISSN 0091-3057.

- ↑ Can You Get Sick From Dirty Bong Water?

- ↑ https://www.maryjanetokes.com/dirty-bong-the-dangers-of-using-one/

- ↑ The Dangers of a Dirty Bong, 2018

- ↑ Handbook of Pharmacy Education, Harmen R.J., 2001, Pg 169

- ↑ Dope Tips II dope tips, reducing cannabis related harms, tips for safer use of cannabis use in nz, using marijuana

- ↑ Ask Erowid : ID 3139 : Do vaporizers work with Salvia divinorum?

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Kooragayalu, S; El-Zarif, S; Jariwala, S. doi:10.1016/j.rmcr.2020.100997. PMC 6997893

. PMID 32042584 //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6997893. Missing or empty

. PMID 32042584 //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6997893. Missing or empty |title=(help) - ↑ "Vaping changes oral microbiome and raises infection risk". www.medicalnewstoday.com (in English). 14 March 2020.

- ↑ Mughal, Mohsin Sheraz; Dalmacion, Denise Lauren V.; Mirza, Hasan Mahmood; Kaur, Ikwinder Preet; Dela Cruz, Maria Amanda; Kramer, Violet E. (1 January 2020). "E-cigarette or vaping product use associated lung injury, (EVALI) - A diagnosis of exclusion". Respiratory Medicine Case Reports (in English). p. 101174. doi:10.1016/j.rmcr.2020.101174.

- ↑ Lestari, Kusuma S.; Humairo, Mika Vernicia; Agustina, Ukik (July 11, 2018). "Formaldehyde Vapor Concentration in Electronic Cigarettes and Health Complaints of Electronic Cigarettes Smokers in Indonesia". Journal of Environmental and Public Health. 2018: 1–6. doi:10.1155/2018/9013430

. ISSN 1687-9805. PMC 6076960

. ISSN 1687-9805. PMC 6076960  . PMID 30105059.

. PMID 30105059.

- ↑ "Erowid Online Books : "TIHKAL" - #38 5-MEO-DMT". www.erowid.org.

- ↑ Evans, S. M., Cone, E. J., Henningfield, J. E. (1 December 1996). "Arterial and venous cocaine plasma concentrations in humans: relationship to route of administration, cardiovascular effects and subjective effects". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 279 (3): 1345–1356. ISSN 0022-3565.

- ↑ http://www.ajol.info/index.php/sajr/article/viewFile/34461/6388. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Gordy S, Rowell S (January 2013). "Vascular air embolism". International Journal of Critical Illness and Injury Science. 3 (1): 73–76. doi:10.4103/2229-5151.109428. PMC 3665124

. PMID 23724390.

. PMID 23724390.

- ↑ Craven, R. (December 2007). "Ketamine". Anaesthesia. 62 (s1): 48–53. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05298.x. ISSN 0003-2409.

- ↑ Aungst, B. J., Rogers, N. J., Shefter, E. (1 January 1988). "Comparison of nasal, rectal, buccal, sublingual and intramuscular insulin efficacy and the effects of a bile salt absorption promoter". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 244 (1): 23–27. ISSN 0022-3565.

- ↑ Fentanyl Transdermal Patch: MedlinePlus Drug Information

- ↑ Lo D, Cobbs L, Chua M, Young J, Haberman ID, Modi Y. "Eye Dropping"-A Case Report of Transconjunctival Lysergic Acid Diethylamide Drug Abuse. Cornea. 2018 Oct;37(10):1324-1325. PMID: 30004961. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000001692.