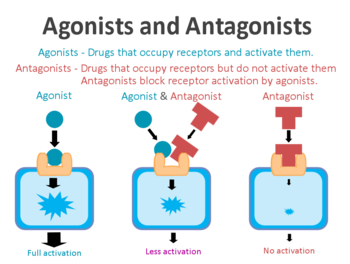

Agonist

An agonist is a chemical that binds to the receptor of a cell and activates the receptor to cause a physiological response. An agonist initiates the same reaction typically produced by the binding of an endogenous ligand (such as a hormone or neurotransmitter) with a receptor.[1] A substance's ability to affect a given receptor is dependent on the substance's affinity and intrinsic efficacy towards that receptor. The affinity of a substance describes the strength of attraction between it and a given receptor, and consequently its ability to bind to that receptor. A substance with a high affinity for a receptor has a high likelihood of binding to it, while a substance with a low affinity has a lesser degree of attraction towards a receptor.

This contrasts the efficacy of a substance, which describes a substance's capacity to produce a response when bound to a receptor. A substance with high efficacy will produce a proportionally stronger effect than a substance of lower efficacy occupying the same number of receptors. The maximum efficacy of a substance reflects the greatest attainable response to a particular substance on a receptor set regardless of dose. A substance with a high efficacy may need to occupy fewer receptors to produce maximum effects, meaning it will not produce stronger effects beyond a certain dosage.

In contrast to an agonist, an antagonist is a chemical that binds to the receptor of a cell without causing a physiological response. Receptor antagonists work by blocking or diminishing the effects produced by endogenous or substance-induced agonism of a receptor.

Types of agonists

Receptors can be activated by chemicals produced by the body (endogenous) or chemicals from outside of the body (exogenous). Therefore, an endogenous agonist for a particular receptor is a chemical produced in the body that binds to and activates that receptor. For example, serotonin is the endogenous agonist of serotonin receptors.

Agonists

There are several types of agonist:

- A superagonist is an agonist that produces a greater effect from the receptor than the endogenous agonist, and therefore has an efficacy of over 100%.

- A full agonist binds and activates a receptor with an efficacy equal to the endogenous agonist. For example, heroin mimics the action of endorphins on μ-opioid receptors in the nervous system.

- A partial agonist binds and activates a receptor with less efficacy than the endogenous agonist. For example, psilocin is a partial agonist of the 5-HT2A receptor.

Inverse agonists

An inverse agonist is an agent that binds to the same receptor as an agonist, but triggers the opposite pharmacological effect of a receptor agonist. Inverse agonists can only act on receptors with constitutive activity; these receptors produce a biological response without the presence of an agonist. An agonist increases a receptor activity above its baseline, while an inverse agonist decreases the receptor activity below its baseline. For example, naloxone is a partial inverse agonist to μ-opioid receptors.

Allosteric modulators

An allosteric modulator is a substance which indirectly influences (modulates) the effects of an agonist or inverse agonist at a target protein (for example, a receptor). Allosteric modulators bind to a site distinct from that of the agonist binding site. Usually they induce a change within the protein structure. A positive allosteric modulator induces an amplification, while a negative modulator induces an attenuation of the effects of the ligand without triggering a functional activity on its own in the absence of the ligand.

Partial agonists

A partial agonist is a substance that activates a receptor but only has partial efficacy in comparison to a full agonist. As a result, partial agonists may have unique properties that full agonists or inverse agonists lack. Some partial agonists, such as buprenorphine, have a ceiling effect, where the subjective effects of the substance do not get any stronger past a certain dose. Partial agonists may also behave as an antagonist in the presence of a full agonist. Buprenorphine, a partial agonist of the μ-opioid receptor, behaves as an antagonist in the presence of other opioids such as heroin. An individual who is dependent on opioids will go into withdrawal if they take buprenorphine while opioids are still in their system due to buprenorphine's antagonistic effects.

See also

External links

References